Cell-associated HIV mucosal transmission: The neglected pathway

|

Dr. Deborah Anderson from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and her colleagues are challenging dogma about the transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Most research has focused on infection by free viral particles, while this group proposes that HIV is also transmitted by infected cells. While inside cells, HIV is protected from antibodies and other antiviral factors, and cell-to-cell virus transmission occurs very efficiently through intercellular synapses. The Journal of Infectious Diseases (JID) has devoted their December supplement to this important and understudied topic.

The 10 articles, four from researchers at BUSM, present the case for cell-associated HIV transmission as an important element contributing to the HIV epidemic. Anderson chides fellow researchers for not using cell-associated HIV in their transmission models: “The failure of several recent vaccine and microbicide clinical trials to prevent HIV transmission may be due in part to this oversight.”

Approximately 75 million people in the world have been infected with HIV-1 since the epidemic started over 30 years ago, mostly through sexual contact and maternal-to-child transmission. A series of vaccine and microbicide clinical trials to prevent HIV transmission have been unsuccessful, and scientists are returning to the drawing board to devise new approaches. The JID supplement advocates for new strategies that target HIV-infected cells in mucosal secretions.

New technique provides novel approach to diagnosing ciliopathies

|

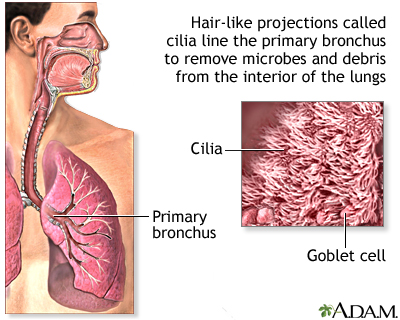

Cilia, the cell’s tails and antennas, are among the most important biological structures. They line our windpipe and sweep away all the junk we inhale; they help us see, smell and reproduce. When a mutation disrupts the function or structure of cilia, the effects on the human body are devastating and sometimes lethal.

The challenge in diagnosing, studying and treating these genetic disorders, called ciliopathies, is the small size of cilia—about 500-times thinner than a piece of paper. It’s been difficult to examine them in molecular detail until now.

Professor Daniela Nicastro and postdoctoral fellow Jianfeng Lin have captured the highest-resolution images of human cilia ever, using a new approach developed jointly with Lawrence Ostrowski and Michael Knowles from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. They reported on the approach in a recent issue of Nature Communications.

About 20 different ciliopathies have been identified so far, including primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) and polycystic kidney disease (PKD), two of the most common ciliopathies. They are typically diagnosed through genetic screening and examination of a patient’s cilia under a conventional electron microscope.

UTSW researchers identify a therapeutic strategy that may treat a childhood neurological disorder

|

UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have identified a possible therapy to treat neurofibromatosis type 1 or NF1, a childhood neurological disease characterized by learning deficits and autism that is caused by inherited mutations in the gene encoding a protein called neurofibromin.

Researchers initially determined that loss of neurofibromin in mice affects the development of the part of the brain called the cerebellum, which is responsible for balance, speech, memory, and learning.

The research team, led by Dr. Luis F. Parada, Chairman of Developmental Biology, next discovered that the anatomical defects in the cerebellum that arise in their mouse model of NF1 could be reversed by treating the animals with a molecule that counteracts the loss of neurofibromin.

“Children with neurofibromatosis have a high incidence of intellectual deficits and autism, syndromes that have been linked to the cerebellum and cortex,” said Dr. Parada, Director of the Kent Waldrep Foundation Center for Basic Neuroscience Research and holder of the Diana K. and Richard C. Strauss Distinguished Chair in Developmental Biology and the Southwestern Ball Distinguished Chair in Nerve Regeneration Research at UT Southwestern. “Our findings in these mouse models suggest that despite embryonic loss of the gene, therapies after birth may be able to reverse some aspects of the disease.”