Infections

Many European countries ill-prepared to prevent and control the spread of viral hepatitis

|

Many countries in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region are facing limitations in conducting chronic viral hepatitis disease surveillance, assessing the burden of disease and measuring the impact of interventions, according to results revealed today at The International Liver Congress™ 2015.

The study highlights that less than one-third (27%) of WHO European Member States have national strategies in place that contain a surveillance component. Furthermore, only 64% have a national surveillance system for chronic hepatitis B and 61% for chronic hepatitis C.

The study also reveals the main areas in which governments would like the WHO’s support:

Development of national plans for viral hepatitis prevention and control (39%)

Estimation of the national burden of viral hepatitis (34%)

Surveillance (23%)

HPV vaccination not associated with increase in sexually transmitted infections

|

A barrier to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination has been the concern that it may promote unsafe sexual activity, but a new study of adolescent girls finds that HPV vaccination was not associated with increases in sexually transmitted infections (STIs), according to an article published online by JAMA Internal Medicine.

Nearly one-quarter of U.S. females between the ages 14 and 19 and 45 percent of women between the ages of 20 and 24 are affected by HPV. The HPV vaccination can prevent cervical, vulvar and vaginal cancers and genital warts caused by certain HPV strains. Still, HPV vaccination rates remain low in the United States and, by 2013, only 57 percent of females between the ages of 13 and 17 had received at least one dose, whereas only 38 percent had received all three recommended doses, according to the study background.

Anupam B. Jena, M.D., Ph.D., of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors used a large insurance database of females (ages 12 to 18) from 2005 through 2010 to examine STIs among girls who were vaccinated and those who were not.

Hepatitis C more prevalent than HIV/AIDS or Ebola yet lacks equal attention

|

More than 180 million people in the world have hepatitis C, compared with the 34 million with HIV/AIDS and the roughly 30,000 who have had Ebola. Yet very little is heard about the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the way of awareness campaigns, research funding or celebrity fundraisers.

One of the global regions highly affected by hepatitis C is West Africa. In developed countries, hepatitis C, a blood-borne disease, is transmitted through intravenous (IV) drug use. “In West Africa, we believe that there are many transmission modes and they are not through IV drug use, but through cultural and every day practices,” says Jennifer Layden, MD, PhD principal investigator on a study recently published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. “In this study, tribal scarring, home birthing and traditional as opposed to hospital based circumcision procedures, were associated with hepatitis C infection in Ghana.”

The study was conducted by HepNet, an international multidisciplinary group of physicians and scientists. “The other important finding was that a high percentage of individuals who tested positive for HCV had evidence of active infection,” says Layden. “This illustrates the need for treatment.”

Discovering the source of the disease and a target population, she says, will aid in the next step of the research: how to protect and prevent the disease in Ghana.

To curb hepatitis C, test and treat inmates

|

Problematic as it is for society, the high incarceration rate in the United States presents an important public health opportunity, according to a new “Perspective” article in the New England Journal of Medicine. It could make staving off the worst of the oncoming hepatitis C epidemic considerably easier.

Nearly 4 million Americans may be infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Many of them don’t know they carry HCV, which can take decades to make them ill with cirrhosis, cancer, or liver failure. About a million people could die because of HCV by 2060, the authors wrote, and many who are saved will have required critical and costly treatments, including liver transplants.

“We know this is going to come crashing down on us,” said lead author Dr. Josiah D. Rich, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Brown University and director of the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights at The Miriam Hospital. “It’s already starting to come crashing down. The next 10 to 20 years are going to be ugly.”

The single best setting for fighting the epidemic is U.S. prisons and jails, where more than 10 million people cycle through each year. In part because a major means of HCV transmission is through injection drug use, a large portion of the nation’s infected population passes through the criminal justice system. In the journal, for example, Rich and his coauthors estimate that one in six inmates is infected and one in three infected Americans ends up locked up for at least a little time in their lives.

Vinegar kills tuberculosis and other mycobacteria

|

The active ingredient in vinegar, acetic acid, can effectively kill mycobacteria, even highly drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an international team of researchers from Venezuela, France, and the US reports in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

Acetic acid might be used as an inexpensive and non-toxic disinfectant against drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) bacteria as well as other stubborn, disinfectant-resistant mycobacteria.

Work with drug-resistant tuberculosis bacteria carries serious biohazard risks. Chlorine bleach is often used to disinfect TB cultures and clinical samples, but bleach is toxic and corrosive. Other effective commercial disinfectants can be too expensive for TB labs in the resource-poor countries where the majority of TB occurs.

“Mycobacteria are known to cause tuberculosis and leprosy, but non-TB mycobacteria are common in the environment, even in tap water, and are resistant to commonly used disinfectants. When they contaminate the sites of surgery or cosmetic procedures, they cause serious infections. Innately resistant to most antibiotics, they require months of therapy and can leave deforming scars.” says Howard Takiff, senior author on the study and head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics at the Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Investigation (IVIC) in Caracas.

New strategy emerges for fighting drug-resistant malaria

|

Malaria is one of the most deadly infectious diseases in the world today, claiming the lives of over half a million people every year, and the recent emergence of parasites resistant to current treatments threatens to undermine efforts to control the disease. Researchers are now onto a new strategy to defeat drug-resistant strains of the parasite. Their report appears in the journal ACS Chemical Biology.

Christine Hrycyna, Rowena Martin, Jean Chmielewski and colleagues point out that the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which causes the most severe form of malaria, is found in nearly 100 countries that, all totaled, are home to about half of the world’s population. Every day, P. falciparum and its relatives hitch rides via mosquitoes to find a human home. An effective vaccine remains elusive and the continuing emergence of drug-resistant parasites is cause for alarm. The good news is that these scientists have designed compounds that work against P. falciparum strains that are resistant to drugs such as chloroquine. The team wanted to understand how these compounds worked and to develop new candidate antimalarials.

In the lab, the scientists designed and tested a set of molecules called quinine dimers, which were effective against sensitive parasites, and, surprisingly, even more effective against resistant ones. The compounds have an additional killing effect on the drug-resistant parasites because the compounds bind to and block the resistance-conferring protein. This resensitizes the parasites to chloroquine, and appears to block the normal function of the resistance protein, killing the parasite. “This highlights the potential for devising new antimalarial therapies that exploit inherent weaknesses in a key resistance mechanism of P. falciparum,” they state.

Toys, books, cribs harbor bacteria for long periods, study finds

|

Numerous scientific studies have concluded that two common bacteria that cause colds, ear infections, strep throat and more serious infections cannot live for long outside the human body. So conventional wisdom has long held that these bacteria won’t linger on inanimate objects like furniture, dishes or toys.

But University at Buffalo research published today in Infection and Immunity shows that Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes do persist on surfaces for far longer than has been appreciated. The findings suggest that additional precautions may be necessary to prevent infections, especially in settings such as schools, daycare centers and hospitals.

“These findings should make us more cautious about bacteria in the environment since they change our ideas about how these particular bacteria are spread,” says senior author Anders Hakansson, PhD, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology in the UB School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. “This is the first paper to directly investigate that these bacteria can survive well on various surfaces, including hands, and potentially spread between individuals.”

S. pneumoniae, a leading cause of ear infections in children and morbidity and mortality from respiratory tract infections in children and the elderly, is widespread in daycare centers and a common cause of hospital infections, says Hakansson. And in developing countries, where fresh water, good nutrition and common antibiotics may be scarce, S. pneumoniae often leads to pneumonia and sepsis, killing one million children every year.

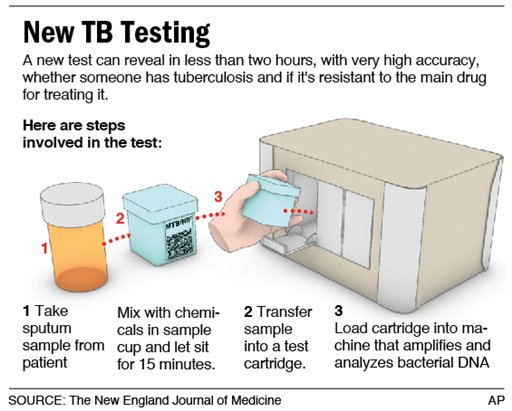

California high school to test students for tuberculosis

|

Some 1,800 students and staff at a southern California high school are to be screened for tuberculosis on Friday, after one pupil was diagnosed with the disease and dozens more may have been infected, health officials said.

The mandatory medical screening at Indio High School about 135 miles outside Los Angeles comes after 45 students out of 131 who were screened for the illness this week tested positive for possible exposure.

The numbers of those potentially infected were higher than expected, but the “the likelihood of the illness being passed from one person to the next is remote,” said Cameron Kaiser, a Riverside County health official who ordered the expanded school-wide testing.

TB Vaccine May Work Against Multiple Sclerosis

|

A vaccine normally used to thwart the respiratory illness tuberculosis also might help prevent the development of multiple sclerosis, a disease of the central nervous system, a new study suggests.

In people who had a first episode of symptoms that indicated they might develop multiple sclerosis (MS), an injection of the tuberculosis vaccine lowered the odds of developing MS, Italian researchers report.

“It is possible that a safe, handy and cheap approach will be available immediately following the first [episode of symptoms suggesting MS],” said study lead author Dr. Giovanni Ristori, of the Center for Experimental Neurological Therapies at Sant’Andrea Hospital in Rome.

But, the study authors cautioned that much more research is needed before the tuberculosis vaccine could possibly be used against multiple sclerosis.

Tuberculosis: Nature has a double-duty antibiotic up her sleeve

|

Technology has made it possible to synthesize increasingly targeted drugs. But scientists still have much to learn from Mother Nature. Pyridomycin, a substance produced by non-pathogenic soil bacteria, has been found to be a potent antibiotic against a related strain of bacteria that cause tuberculosis. The EPFL scientists who discovered this unexpected property now have a better understanding of how the molecule functions. Its complex three-dimensional structure allows it to act simultaneously on two parts of a key enzyme in the tuberculosis bacillus, and in doing so, dramatically reduce the risk that the bacteria will develop multiple resistances. The researchers, along with their colleagues at ETH Zurich, have published their results in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Stewart Cole, director of EPFL’s Global Health Institute, led a team that discovered the anti-tuberculosis effect of pyridomycin in 2012. By inhibiting the action of the “InhA” enzyme, pyridomycin literally caused the thick lipid membrane of the bacterium to burst. Now the scientists understand how the molecule does this job.

Dual anti-mutation ability

The tuberculosis bacillus needs the InhA enzyme along with what scientists refer to as a “co-factor,” which activates the enzyme, in order to manufacture its membrane. The scientists discovered that pyridomycin binds with the co-factor, neutralizing it.

Treatment target identified for a public health risk parasite

|

In the developing world, Cryptosporidium parvum has long been the scourge of freshwater. A decade ago, it announced its presence in the United States, infecting over 400,000 people - the largest waterborne-disease outbreak in the county’s history. Its rapid ability to spread, combined with an incredible resilience to water decontamination techniques, such as chlorination, led the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United Sates to add C. parvum to its list of public bioterrorism agents. Currently, there are no reliable treatments for cryptosporidiosis, the disease caused by C. parvum, but that may be about to change with the identification of a target molecule by investigators at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC). The findings of this study have been recently published in the Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (AAC) journal.

“In the young, the elderly and immunocompromised people such as people infected with HIV/Aids, C. parvum is a very dangerous pathogen. Cryptosporidiosis is potentially life-threatening and can result in diarrhea, malnutrition, dehydration and weight loss,” says first author of the study, Dr. Momar Ndao, Director of the National Reference Centre of Parasitology (NRCP) at the MUHC and an Assistant Professor of the Departments of Medicine, Immunology and Parasitology (Division of Infectious Diseases) at McGill University.

The oocysts of C. parvum, which are shed during the infectious stage, are protected from a thick wall that allows them to survive for long periods outside the body as they spread to a new host. C. parvum is a microscopic parasite that lives in the intestinal tract of humans and many other mammals. It is transmitted through the fecal-oral contact with an infected person or animal, or from the ingestion of contaminated water or food. Since the parasite is resistant to chlorine and difficult to filter, cryptosporidiosis epidemics are hard to prevent.

Nearly half of U.S. children late receiving vaccines

|

|

Nearly half of babies and toddlers in the United States aren’t getting recommended vaccines on time, according to a study - and if enough skip vaccines, whole schools or communities could be vulnerable to diseases such as whooping cough and measles.

“What we’re worried about is if (undervaccination) becomes more and more common, is it possible this places children at an increased risk of vaccine-preventable diseases?” said study leader Jason Glanz, with Kaiser Permanente Colorado in Denver.

“It’s possible that some of these diseases that we worked so hard to eliminate (could) come back.”

Glanz and his colleagues analyzed data from eight managed care organizations, including immunization records for about 323,000 children.

MMV develops framework to assess risk of resistance for antimalarial compounds

|

|

Medicines for Malaria Venture has developed a framework to evaluate the risk of resistance for the antimalarial compounds in its portfolio. A paper based on this work: A framework for assessing the risk of resistance for antimalarials in development has been published in the Malaria Journal today.

Resistance defines the longevity of every anti-infective drug, so it is important when developing new medicines for malaria, to check how easily promising antimalarial compounds will select for resistance. Once this is known, it facilitates the prioritization of not only the most efficacious compounds but also the most robust ones.

“By profiling our portfolio as early as possible in terms of resistance liabilities, be they pre-existing or acquired, we are attempting to ensure that none of the compounds will fall to potential resistance,” said Tim Wells, Chief Scientific Officer, MMV, and one of the authors of the paper. “This will also help us cost-effectively accelerate the drug development process, and be prepared in advance with a full resistance profile which is required by regulatory authorities before a new drug can be approved.”

Father of Ga. woman with flesh-eating disease says she’s suffering worst pain of entire ordeal

|

|

The father of a Georgia woman battling a flesh-eating disease says his daughter has been suffering the worst pain of her entire ordeal.

Andy Copeland says his daughter, Aimee, sometimes cries from the pain but stops because crying hurts her stomach. She had resisted taking pain medications in recent days.

Andy Copeland said in a Father’s Day post on his blog that she’s now taking morphine and other medications, but they aren’t enough to block severe pain, which has now spread beyond painful amputation sites.

Georgia woman with flesh-eating disease in “critical” condition

|

|

Georgia woman fighting a flesh-eating bacterial infection was in critical condition at Augusta Hospital on Saturday, a hospital spokeswoman said.

The spokeswoman said she could not comment on whether Aimee Copeland had undergone surgery to remove her hands and right foot, amputations that Copeland’s father had said were pending on Friday. Surgeons had amputated the 24-year-old’s left leg at the hip.

“All I can say is Aimee is still in critical condition,” hospital spokeswoman Barclay Bishop said.

Prayers and messages of support have poured in for Copeland on a Facebook page where her father, Andy Copeland, has chronicled her struggle.