FDA denies approval to wider use of J&J’s blood clot preventer

|

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration denied an approval to a wider use of Johnson & Johnson’s heart drug Xarelto.

The blood-clot preventing drug is already approved for use in multiple indications.

J&J’s unit Janssen Research & Development was seeking approval for using the drug to reduce the risk of heart problems, such as heart attack, stroke or death, in patients with acute coronary syndrome and to reduce the risk of stent thrombosis - a blood clot at the site of the stent.

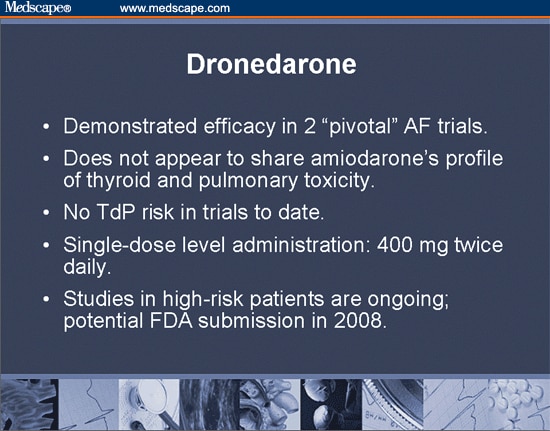

FDA Warns of Potential Risk of Severe Liver Injury With Use of Dronedarone

|

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is notifying healthcare professionals and patients about cases of rare, but severe liver injury, including 2 cases of acute liver failure leading to liver transplant, in patients treated with dronedarone (Multaq).

Information about the potential risk of liver injury from dronedarone is being added to the WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS and ADVERSE REACTIONS sections of the dronedarone labels.

Dronedarone was approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) with a goal of preventing its use in patients with severe heart failure or who have recently been in the hospital for heart failure. In a study of patients with these conditions, patients given dronedarone had a greater than 2-fold increase in risk of death.

Healthcare professionals were reminded to advise patients to contact a healthcare professional immediately if they experience signs and symptoms of hepatic injury or toxicity (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fever, malaise, fatigue, right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, dark urine, or itching) while taking dronedarone.

ADHD drugs not linked to increased stroke risk among children

|

Children who take medication to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) don’t appear to be at increased stroke risk, according to a study presented at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference 2014.

In a study of 2.5 million 2- to 19-year-olds over a 14-year period, researchers compared stimulant medication usage in children diagnosed with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke to stimulant usage in children without stroke. Researchers found no association between stroke risk and the use of ADHD stimulant medications at the time of stroke or at any time prior to stroke.

###

Note: Actual presentation is 5:20 p.m. PT Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2014.

Follow news from the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference 2014 via Twitter: @HeartNews #ISC14.

Laboratory detective work points to potential therapy for rare, drug-resistant cancer

|

University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) scientists have shown that old drugs might be able to do new tricks.

By screening a library of FDA-approved anticancer drugs that previously wouldn’t have been considered as a treatment for a rare type of cancer, UPCI scientists were surprised when they found several potential possibilities to try if the cancer becomes resistant to standard drug treatment.

The discovery, which will be published in the February 15th issue of Cancer Research, demonstrates that high-throughput screening of already FDA-approved drugs can identify new therapies that could be rapidly moved to the clinic.

“This is known as ‘drug repurposing,’ and it is an increasingly promising way to speed up the development of treatments for cancers that do not respond well to standard therapies,” said senior author Anette Duensing, M.D., assistant professor of pathology at UPCI. “Drug repurposing builds upon previous research and development efforts, and detailed information about the drug formulation and safety is usually available, meaning that it can be ready for clinical trials much faster than a brand-new drug.”

Targeting tumors: Ion beam accelerators take aim at cancer

|

EVENT: Advances in the design and operation of particle accelerators built for basic physics research are leading to the rapid evolution of machines that deliver cancer-killing beams. Hear about the latest developments and challenges in this field from a physicist, a radiobiologist, and a clinical oncologist, and participate in a discussion about cost, access, and ethics at a symposium organized by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory (“Targeting Tumors: Ion Beam Accelerators Take Aim at Cancer”) and at a related press briefing—both to be held at the 2014 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

WHEN: Sunday, February 16, 2014, 8:00 a.m. Central Time (symposium) and 11:00 a.m. (press briefing)

WHERE: Symposium: Hyatt Regency Chicago, Grand Ballroom A; Press Briefing: Swissotel, AAAS briefing room, adjacent to the newsroom, second floor.

WEBCAST: For reporters unable to attend the meeting, the press briefing portion will be webcast live and archived in the AAAS meeting newsroom.

Link confirmed between salmon migration, magnetic field

|

A team of scientists last year presented evidence of a correlation between the migration patterns of ocean salmon and the Earth’s magnetic field, suggesting it may help explain how the fish can navigate across thousands of miles of water to find their river of origin.

This week, scientists confirmed the connection between salmon and the magnetic field following a series of experiments at the Oregon Hatchery Research Center in the Alsea River basin. Researchers exposed hundreds of juvenile Chinook salmon to different magnetic fields that exist at the latitudinal extremes of their oceanic range. Fish responded to these “simulated magnetic displacements” by swimming in the direction that would bring that toward the center of their marine feeding grounds.

The study, which was funded by Oregon Sea Grant and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, will be published this month in the forthcoming issue of Current Biology.

“What is particularly exciting about these experiments is that the fish we tested had never left the hatchery and thus we know that their responses were not learned or based on experience, but rather they were inherited,” said Nathan Putman, a postdoctoral researcher at Oregon State University and lead author on the study.

Immune system ‘overdrive’ in pregnant women puts male child at risk for brain disorders

|

Johns Hopkins researchers report that fetal mice - especially males - show signs of brain damage that lasts into their adulthood when they are exposed in the womb to a maternal immune system kicked into high gear by a serious infection or other malady. The findings suggest that some neurologic diseases in humans could be similarly rooted in prenatal exposure to inflammatory immune responses.

In a report on the research published online last week in the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity, the investigators say that the part of the brain responsible for memory and spatial navigation (the hippocampus) was smaller over the long term in the male offspring exposed to the overactive immune system in the womb. The males also had fewer nerve cells in their brains and their brains contained a type of immune cell that shouldn’t be present there.

“Our research suggests that in mice, males may be more vulnerable to the effects of maternal inflammation than females, and the impact may be life long,” says study leader Irina Burd, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of gynecology/obstetrics and neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Integrated Research Center for Fetal Medicine. “Now we wonder if this could explain why more males have diseases such as autism and schizophrenia, which appear to have neurobiological causes.”

For the study, researchers sought to mimic the effects of a maternal infection or other condition that causes inflammation in a pregnant mother. This type of inflammation between 18 and 32 weeks of gestation in humans has been linked to preterm birth as well as an imbalance of immune cells in the brain of the offspring and even death of nerve cells in the brains of those children. Burd and her colleagues used a mouse model to study what happens to the brains of those offspring as they age into adulthood to see if the effects persisted.

Researchers find retrieval practice improves memory in severe traumatic brain injury

|

Kessler Foundation researchers find retrieval practice improves memory in severe traumatic brain injury

Robust results indicate that retrieval practice would improve memory in memory-impaired persons with severe TBI in real-life settings

West Orange, NJ. January 30, 2014. Kessler Foundation researchers have shown that retrieval practice can improve memory in individuals with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). “Retrieval Practice Improves Memory in Survivors of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury,” was published as a brief report in the current issue of Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Volume 95, Issue 2 (390-396) February 2014. The article is authored by James Sumowski, PhD, Julia Coyne, PhD, Amanda Cohen, BA, and John DeLuca, PhD, of Kessler Foundation.

“Despite the small sample size, it was clear that retrieval practice (RP) was superior to other learning strategies in this group of memory-impaired individuals with severe TBI,” explained Dr. Sumowski.

Overexpression of splicing protein in skin repair causes early changes seen in skin cancer

|

Normally, tissue injury triggers a mechanism in cells that tries to repair damaged tissue and restore the skin to a normal, or homeostatic state. Errors in this process can give rise to various problems, such as chronic inflammation, which is a known cause of certain cancers.

“It has been noted that cancer resembles a state of chronic wound healing, in which the wound-healing program is erroneously activated and perpetuated,” says Professor Adrian Krainer of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). In a paper published today in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, a team led by Dr. Krainer reports that a protein they show is normally involved in healing wounds and maintaining homeostasis in skin tissue is also, under certain conditions, a promoter of invasive and metastatic skin cancers.

The protein, called SRSF6, is what biologists call a splicing factor: it is one of many proteins involved in an essential cellular process called splicing. In splicing, an RNA “message” copied from a gene is edited so that it includes only the portions needed to instruct the cell how to produce a specific protein. The messages of most genes can be edited in multiple ways, using different splicing factors; thus, a single gene can give rise to multiple proteins, with distinct functions.

The SRSF6 protein, while normally contributing to wound healing in skin tissue, when overproduced can promote abnormal growth of skin cells and cancer, Krainer’s team demonstrated in experiments in mice. Indeed, they determined the spot on a particular RNA message - one that encodes the protein tenascin C - where SRSF6 binds abnormally, giving rise to alternate versions of the tenascin C protein that are seen in invasive and metastatic cancers.

In the blink of an eye

|

Imagine seeing a dozen pictures flash by in a fraction of a second. You might think it would be impossible to identify any images you see for such a short time. However, a team of neuroscientists from MIT has found that the human brain can process entire images that the eye sees for as little as 13 milliseconds - the first evidence of such rapid processing speed.

That speed is far faster than the 100 milliseconds suggested by previous studies. In the new study, which appears in the journal Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics, researchers asked subjects to look for a particular type of image, such as “picnic” or “smiling couple,” as they viewed a series of six or 12 images, each presented for between 13 and 80 milliseconds.

“The fact that you can do that at these high speeds indicates to us that what vision does is find concepts. That’s what the brain is doing all day long - trying to understand what we’re looking at,” says Mary Potter, an MIT professor of brain and cognitive sciences and senior author of the study.

This rapid-fire processing may help direct the eyes, which shift their gaze three times per second, to their next target, Potter says. “The job of the eyes is not only to get the information into the brain, but to allow the brain to think about it rapidly enough to know what you should look at next. So in general we’re calibrating our eyes so they move around just as often as possible consistent with understanding what we’re seeing,” she says.

Low national funding for LGBT health research contributes to inequities, analysis finds

|

Only one-half of 1 percent of studies funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between 1989 and 2011 concerned the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, contributing to the perpetuation of health inequities, according to a University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health-led analysis.

The findings, which grew from the Fenway Institute’s Summer Institute in LGBT Population Health in Boston and continued at Pitt Public Health’s Center for LGBT Health Research, are in the February issue of the American Journal of Public Health, published today. The researchers make several recommendations for how to stimulate LGBT-related research.

“The NIH is the world’s largest source of health research funding and has placed a low priority on LGBT health research,” said Robert W.S. Coulter, M.P.H., a doctoral student in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences. “In general, LGBT people experience stigma associated with their sexual and gender minority status, disproportionate behavioral risks and psychosocial health problems, and higher chronic disease risk factors than their non-LGBT counterparts. Increased NIH funding for research on these topics, particularly focusing on evidence-based interventions to reduce health inequities, could help alleviate these negative health outcomes.”

About 3.5 percent of the U.S. adult population is estimated to be gay, lesbian or bisexual, according to recent research based on national- and state-level population surveys.

New strategy emerges for fighting drug-resistant malaria

|

Malaria is one of the most deadly infectious diseases in the world today, claiming the lives of over half a million people every year, and the recent emergence of parasites resistant to current treatments threatens to undermine efforts to control the disease. Researchers are now onto a new strategy to defeat drug-resistant strains of the parasite. Their report appears in the journal ACS Chemical Biology.

Christine Hrycyna, Rowena Martin, Jean Chmielewski and colleagues point out that the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which causes the most severe form of malaria, is found in nearly 100 countries that, all totaled, are home to about half of the world’s population. Every day, P. falciparum and its relatives hitch rides via mosquitoes to find a human home. An effective vaccine remains elusive and the continuing emergence of drug-resistant parasites is cause for alarm. The good news is that these scientists have designed compounds that work against P. falciparum strains that are resistant to drugs such as chloroquine. The team wanted to understand how these compounds worked and to develop new candidate antimalarials.

In the lab, the scientists designed and tested a set of molecules called quinine dimers, which were effective against sensitive parasites, and, surprisingly, even more effective against resistant ones. The compounds have an additional killing effect on the drug-resistant parasites because the compounds bind to and block the resistance-conferring protein. This resensitizes the parasites to chloroquine, and appears to block the normal function of the resistance protein, killing the parasite. “This highlights the potential for devising new antimalarial therapies that exploit inherent weaknesses in a key resistance mechanism of P. falciparum,” they state.

Tweaking MRI to track creatine may spot heart problems earlier, Penn Medicine study suggests

|

A new MRI method to map creatine at higher resolutions in the heart may help clinicians and scientists find abnormalities and disorders earlier than traditional diagnostic methods, researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania suggest in a new study published online today in Nature Medicine. The preclinical findings show an advantage over less sensitive tests and point to a safer and more cost-effective approach than those with radioactive or contrasting agents.

Creatine is a naturally occurring metabolite that helps supply energy to all cells through creatine kinase reaction, including those involved in contraction of the heart. When heart tissue becomes damaged from a loss of blood supply, even in the very early stages, creatine levels drop. Researchers exploited this process in a large animal model with a method known as CEST, or chemical exchange saturation transfer, which measures specific molecules in the body, to track the creatine on a regional basis.

The team, led by Ravinder Reddy, PhD, professor of Radiology and director of the Center for Magnetic Resonance and Optical Imaging at Penn Medicine, found that imaging creatine through CEST MRI provides higher resolution compared to standard magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), a commonly used technique for measuring creatine. However, its poor resolution makes it difficult to determine exactly which areas of the heart have been compromised.

“Measuring creatine with CEST is a promising technique that has the potential to improve clinical decision making while treating patients with heart disorders and even other diseases, as well as spotting problems sooner,” said Reddy. “Beyond the sensitivity benefits and its advantage over MRS, CEST doesn’t require radioactive or contrast agents used in MRI, which can have adverse effects on patients, particularly those with kidney disease, and add to costs.”

Cancer drug protects against diabetes

|

New research shows that low doses of a cancer drug protect against the development of type 1 diabetes in mice. At the same time, the medicine protects the insulin-producing cells from being destroyed. The study is headed by researchers from the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, and has just been published in the distinguished scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

Very low doses of a drug used to treat certain types of cancer protect the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas and prevent the development of diabetes mellitus type 1 in mice. The medicine works by lowering the level of so-called sterile inflammation. The findings have been made by researchers from the University of Copenhagen, the Technical University of Denmark and the University of Southern Denmark working with researchers in Belgium, Italy, Canada, Netherlands and the USA.

“Diabetes is a growing problem worldwide. Our research shows that very low doses of anticancer drugs used to treat lymphoma - so-called lysine deacetylase inhibitors - can reset the immune response to not attack the insulin-producing cells. We find fewer immune cells in the pancreas, and more insulin is produced when we give the medicine in the drinking water to mice that would otherwise develop type 1 diabetes,” says postdoc Dan Ploug Christensen, who is the first author on the article and responsible for the part of the experimental work carried out in Professor Thomas Mandrup-Poulsen’s laboratory at the Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

Fresh faced: Looking younger for longer

|

Newcastle University researchers have identified an antioxidant Tiron, which offers total protection against some types of sun damage and may ultimately help our skin stay looking younger for longer.

Publishing in The FASEB Journal, the authors describe how in laboratory tests, they compared the protection offered against either UVA radiation or free radical stress by several antioxidants, some of which are found in foods or cosmetics. While UVB radiation easily causes sunburn, UVA radiation penetrates deeper, damaging our DNA by generating free radicals which degrades the collagen that gives skin its elastic quality.

The Newcastle team found that the most potent anti-oxidants were those that targeted the batteries of the skin cells, known as the mitochondria. They compared these mitochondrial-targeted anti-oxidants to other non-specific antioxidants such as resveratrol, found in red wine, and curcumin found in curries, that target the entire cell. They found that the most potent mitochondrial targeted anti-oxidant was Tiron which provided 100%, protection of the skin cell against UVA sun damage and the release of damaging enzymes causing stress-induced damage.